Ogres, Pixies, and Giants: Kazuo Ishiguro’s Improvisations

March 31, 2015, by Doni Wilson

There was a lot of anticipation for Monday night’s Kazuo Ishiguro Inprint Margarett Root Brown reading from, The Buried Giant, his first new novel in ten years. I knew it was sold out—left early, warmed up by listening to his interview with St. John Flynn of Houston Public Media, which you can hear here:

There was a lot of anticipation for Monday night’s Kazuo Ishiguro Inprint Margarett Root Brown reading from, The Buried Giant, his first new novel in ten years. I knew it was sold out—left early, warmed up by listening to his interview with St. John Flynn of Houston Public Media, which you can hear here:

Just like everyone else streaming into the beautiful Wortham Center, I was excited. He was on a “limited” U.S. book tour and Houston had made the cut.

Multiple nominee for the prestigious Man Booker Prize, Ishiguro won in 1989 for his best known work, The Remains of the Day, which was also made into an excellent film starring Sir Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson. Never Let Me Go had also been made into a film, and Ishiguro has been listed as one of the 50 greatest British writers since 1948 by The Times. Recipient of the OBE award from the British Crown, he is a palpable force in English letters, tending to experiment stylistically while hovering on similar themes: self-denial, acceptance of fate, the dance of time with potential and real regrets.

Multiple nominee for the prestigious Man Booker Prize, Ishiguro won in 1989 for his best known work, The Remains of the Day, which was also made into an excellent film starring Sir Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson. Never Let Me Go had also been made into a film, and Ishiguro has been listed as one of the 50 greatest British writers since 1948 by The Times. Recipient of the OBE award from the British Crown, he is a palpable force in English letters, tending to experiment stylistically while hovering on similar themes: self-denial, acceptance of fate, the dance of time with potential and real regrets.

Although born in Japan, and influenced by the culture of the Samurai in interesting ways, Ishiguro comes across as thoroughly English, having lived there since he was five in 1960. He did not speak English, but enjoyed American Westerns on television, and later, became hugely influenced by the novels of Charlotte Bronte, particularly Jane Eyre and Villette. Ishiguro began as a singer-songwriter, interested in jazz and its improvisational modes—an influence that has carried over to his writing.

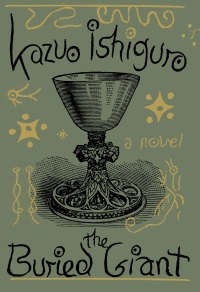

Ishiguro read from Chapter 11 of The Buried Giant, which takes place around 490 AD, a rather murky period of English history after the British Romans have left, and while the Anglo-Saxons are just settling in. His characters are the indigenous Britons who were eventually obliterated—giving Ishiguro wide latitude in representing them—lost people who are looking for a lost son. It is a chapter full of physical challenges (“It was bitingly cold on the river”), but the psychological atmosphere is what stays with the audience. The story is part of a longer journey, concerned with collective and individual forgetting, and the atmosphere conspires to aid and abet that enterprise: “This mist makes us forget so much,” one of the characters says, but it is a reminder to everyone about how the forces of memory are easily challenged.

Ishiguro read from Chapter 11 of The Buried Giant, which takes place around 490 AD, a rather murky period of English history after the British Romans have left, and while the Anglo-Saxons are just settling in. His characters are the indigenous Britons who were eventually obliterated—giving Ishiguro wide latitude in representing them—lost people who are looking for a lost son. It is a chapter full of physical challenges (“It was bitingly cold on the river”), but the psychological atmosphere is what stays with the audience. The story is part of a longer journey, concerned with collective and individual forgetting, and the atmosphere conspires to aid and abet that enterprise: “This mist makes us forget so much,” one of the characters says, but it is a reminder to everyone about how the forces of memory are easily challenged.

The shock of the chapter, and maybe even the entire novel, is the appearance of entities such as pixies (they seem utterly disgusting), ogres, and giants—a far cry from the butler’s quarters of The Remains of the Day. There is Sir Gawain—yes, of Green Knight fame—and Ishiguro suggests that he is, like many of his characters, “out of time”—that is, they have a certain nobility or set of ethics that seems obsolete, anachronistic, awkward. They reveal what is no longer tenable and relegated to history or the literary imagination.

The shock of the chapter, and maybe even the entire novel, is the appearance of entities such as pixies (they seem utterly disgusting), ogres, and giants—a far cry from the butler’s quarters of The Remains of the Day. There is Sir Gawain—yes, of Green Knight fame—and Ishiguro suggests that he is, like many of his characters, “out of time”—that is, they have a certain nobility or set of ethics that seems obsolete, anachronistic, awkward. They reveal what is no longer tenable and relegated to history or the literary imagination.

In the Q&A session, led by novelist and University of Houston Honors College faculty member Robert Cremins, Cremins notes the departure from Ishiguro’s previous works in The Buried Giant. Ishiguro agrees that this novel “is not a typical kind of thing for me at all,” and that the “mythical landscape” is intended for him to explore, microcosmically, the issues of nations’ “remembering and forgetting,” which was in part inspired by the dissolution of Yugoslavia and even South Africa after apartheid. Communal forgetting, Ishiguro explains, even in a deliberate form, may reflect “the need to avoid another cycle of violence.”

Ishiguro agrees that this novel “is not a typical kind of thing for me at all,” and that the “mythical landscape” is intended for him to explore, microcosmically, the issues of nations’ “remembering and forgetting,” which was in part inspired by the dissolution of Yugoslavia and even South Africa after apartheid. Communal forgetting, Ishiguro explains, even in a deliberate form, may reflect “the need to avoid another cycle of violence.”

Ishiguro’s point that the “dark passages buried” in communal or national history can also be identified in more immediate relationships: parents to children, friendships, even marriages, in which the “buried passages” and unspoken ruptures are psychologically necessary to keep them intact. His most profound question, both for the novel and for the audience, is “How much should we actually remember?”

Expanding on that thought, Ishiguro asks, is “love ‘genuine’ if it is based on suppression” or a limited acknowledgment of history and truth? He is interested in the notion of “collective memory lapses” and “some kind of group amnesia,” and one cannot help but think of the social lubricant of smiles and denial that has been present in American southern culture, in both charming and disturbing incarnations.

Expanding on that thought, Ishiguro asks, is “love ‘genuine’ if it is based on suppression” or a limited acknowledgment of history and truth? He is interested in the notion of “collective memory lapses” and “some kind of group amnesia,” and one cannot help but think of the social lubricant of smiles and denial that has been present in American southern culture, in both charming and disturbing incarnations.

When asked about his process as an artist, Ishiguro charmingly admits to having “slightly geeky writer’s notebooks”—some left since the 1980s—in which he has his own set of buried passages that he leaves behind for long periods of time, often even years, and that sometimes provide the seed of future stories. Ishiguro quips that his wife, Lorna, knew him before he was a writer, when he was an aspiring musician, and still thinks of him as a writing ”upstart”—an amusing part of his interview. Yet his accomplishments as a writer are indisputable, even if he confesses to tending to “have these ideas” with “two or three pieces of the jigsaw missing” before he fully brings a work to fruition.

If Ishiguro’s early works were “warnings to himself” about how to live, “a way of making sure—forcing me to have a perspective on the life I was leading,” The Buried Giant is about something else: “less warnings, something else.” Here, he is more like the musician—taking risks, improvising, even if it means going far back to Dark Ages Britain, conjuring trolls, flinging pixies and pixie dust on the page. He is interested in what corrupts—the corruption of “a decent thing” that ultimately destroys it, and the role memory and recognition play in that process. If something is “out of its time”—whether it be a knight, or English gentleman, or a lone cowboy, what does that mean about time?

If Ishiguro’s early works were “warnings to himself” about how to live, “a way of making sure—forcing me to have a perspective on the life I was leading,” The Buried Giant is about something else: “less warnings, something else.” Here, he is more like the musician—taking risks, improvising, even if it means going far back to Dark Ages Britain, conjuring trolls, flinging pixies and pixie dust on the page. He is interested in what corrupts—the corruption of “a decent thing” that ultimately destroys it, and the role memory and recognition play in that process. If something is “out of its time”—whether it be a knight, or English gentleman, or a lone cowboy, what does that mean about time?

One of Ishiguro’s last comments is his acknowledgment of the “large element of self-denial in people” and his observations that “most of the time people accept the fate given to them”—although this acceptance is in itself a curious choice, and one that has proven endlessly fascinating in his works. His “key method” for all of his work is controlling “the element of surprise—or the lack of it.”

Ishiguro’s latest novel is certainly a surprise—both in terms of setting and form, part of what Cremins calls his ability to keep the reader “constantly on your toes.” But Ishiguro is not jaded about these experimentations. He says, “the reality of it is that quite a lot of decisions I make are more intuitive,” and he fears writers feeling like they have to have reasons to justify every aesthetic decision they make.

Often, he reminds the audience, he just writes something not because of any particular intellectual reasons, but “because it sounds better that way.” He tells the audience that he thinks that “writers become too self-conscious.” He thinks it is better to be more like a painter, a musician. Better to allow giants, ogres, and pixies on the canvas, in the song.