How to Become U. S. Poet Laureate

April 19, 2012, by Rich Levy

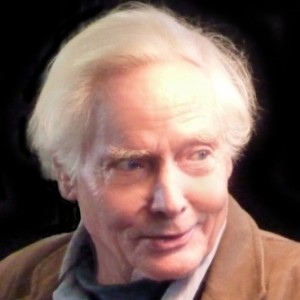

In anticipation of former Poet Laureate W. S. Merwin’s visit to Houston to close out the 2011-2012 Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series next Monday, Inprint Executive Director Rich Levy chatted with Rob Casper, who serves as Head of the Poetry and Literature Center of the Library of Congress, about one of the nation’s most unique and mysterious “jobs” —the position of U. S. Poet Laureate.

In anticipation of former Poet Laureate W. S. Merwin’s visit to Houston to close out the 2011-2012 Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series next Monday, Inprint Executive Director Rich Levy chatted with Rob Casper, who serves as Head of the Poetry and Literature Center of the Library of Congress, about one of the nation’s most unique and mysterious “jobs” —the position of U. S. Poet Laureate.

Rich: Rob, how is the U.S. Poet Laureate selected?

![]() Rob: There is a lot of mystery surrounding the Poet Laureate selection, but really it’s quite simple. For the past two years I helped the Librarian of Congress, James H. Billington, in the selection process for the Poet Laureate Consultant of Poetry (the official title). The Librarian has a Congressional mandate to select the Poet Laureate.

Rob: There is a lot of mystery surrounding the Poet Laureate selection, but really it’s quite simple. For the past two years I helped the Librarian of Congress, James H. Billington, in the selection process for the Poet Laureate Consultant of Poetry (the official title). The Librarian has a Congressional mandate to select the Poet Laureate.

I didn’t work at the Library of Congress when William Merwin was selected; however, from what I can tell the process worked roughly the same as it did last year, when Dr. Billington selected Philip Levine. (The Poet Laureate serves a one-year term, although several have served additional consecutive terms.) First, I contacted 30 editors, scholars, critics, and nonprofit literary administrators, as well as 10 former Poets Laureate, for nominations. We received 60 nominations in total—half with more than one vote. Dr. Billington and I discussed each nominee in the latter category, and I made several packets with selections for him to review. We spent a number of months looking at batches of poets, and when Dr. Billington decided on a group of finalists he asked me to follow up with two former Poets Laureate, a prominent arts director, and a person of my own choosing for a final review. Right after I provided the results from that review, we had a short discussion and Dr. Billington made his selection.