Puzzling through stories with Peter Turchi

February 4, 2015, by Allyn West

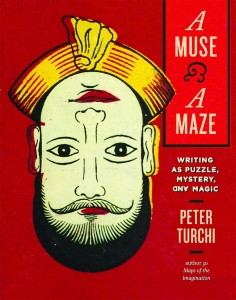

Inprint loves to showcase the best in new books by top local authors. One of the most interesting books to come out in the past year is A Muse and A Maze: Writing as Puzzle, Mystery, and Magic by Houston writer Peter Turchi. Turchi is the author of several books, including Map of the Imagination: Writer as Cartographer, named by The New York Times as one of the 100 Best Nonfiction Books of All Time. Turchi, a faculty member at the University of Houston Creative Writing Program, serves as a frequent interviewer for the Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series.

Some of my favorite books when I was just a li’l egghead were the Encyclopedia Brown stories by Donald Sobol. I went back to a collection of them recently after reading A Muse & A Maze: Writing as Puzzle, Mystery, & Magic, the new book by University of Houston creative writing professor Peter Turchi.

Some of my favorite books when I was just a li’l egghead were the Encyclopedia Brown stories by Donald Sobol. I went back to a collection of them recently after reading A Muse & A Maze: Writing as Puzzle, Mystery, & Magic, the new book by University of Houston creative writing professor Peter Turchi.

The Encyclopedia Brown stories present themselves as mysteries. They concern Leroy, a.k.a. “Encyclopedia,” a 10-year-old “Sherlock Holmes in sneakers,” whose father happens to be the chief of police of Idaville, a town “like many other seaside [ones],” with “lovely beaches, three movie theaters, and four banks.” Except no one, writes Sobol, “got away with breaking the law in Idaville.”

The lawbreakers are your typical seaside layabouts; nothing to see here. Encyclopedia’s primary nemesis is a fledgling sociopath named Bugs Meany, instigator of a gang of would-be toughs called the Tigers who try to scam the other townies. Each chapter begins with an aggrieved victim seeking out Encyclopedia and his sidekick, Sally Kimbell. They ride their bikes to the scene of the crime; the story of the accuser and the story of the accused are told, and Encyclopedia pauses dramatically while Sobol interrupts to direct you to page 64 for “the solution.” In the end, some detail that violates the rate at which water evaporates, or the conventions of elevator repair, or the date when the Liberty Bell was cracked, is the lie that tells the truth. The antique lamp or the champion yodeling toad is returned to the rightful owner, and order is restored.

As a kid, I wasn’t turned off by this formula. I confess that I fashioned myself in Encyclopedia’s image as an insufferable, know-it-all busybody, smarter than his father, and I delighted in the continual thwarting of Bugs’s schemes and my self-alignment on this side of justice. Plus, I was eager to play along, combing the stories to identify which detail would be the one that cracked the case!

Returning to a few of them last month, though, I didn’t delight in much of anything. I found Sobol’s sleight-of-hand to be ham-handed. I wondered when Encyclopedia might begin to resent his father and strike out on his own as a kind of freelance intellectual vigilante, solving crimes in exchange for the contraband Ritalin he swallowed to keep himself awake while memorizing almanacs. And why didn’t he ever invite Sally up to the ol’ treehouse, as it were? I realize that this is as it should be — no one grows up to remain haunted by Goosebumps, right?

But having each case explained away creates a delight roughly equal to the one you feel doing algebra problems and flipping to the back to make sure you get the answers right. Now, though, most of us read for questions. And Turchi’s book gives us a much more adult sense of the pleasures and possibilities of mystery as well as a deeper appreciation for the way we readers puzzle through stories.

Now, though, most of us read for questions. And Turchi’s book gives us a much more adult sense of the pleasures and possibilities of mystery as well as a deeper appreciation for the way we readers puzzle through stories.

The kind of puzzles you find in the Encyclopedia Brown stories are, essentially, already finished. Your job as the reader is to find the one odd-shaped or colored piece, the one that doesn’t “fit,” and then you, too, can feel as though you are helping to keep the streets of Idaville safe. Turchi has something different in mind; he wants to trouble the very way we use the metaphor. “The story as a whole is not a problem with a solution,” he writes. “A story means to lead the reader somewhere. But the destination isn’t a monster, or a pot of gold, or a bit of wisdom. Instead, the destination is something—or several things—to contemplate. The best stories and novels lead the reader not to an explanation, but to a place of wonder.”

“A story means to lead the reader somewhere. But the destination isn’t a monster, or a pot of gold, or a bit of wisdom. Instead, the destination is something—or several things—to contemplate. The best stories and novels lead the reader not to an explanation, but to a place of wonder.”

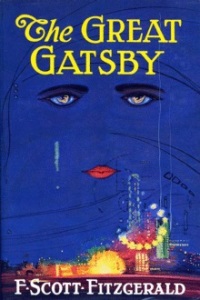

My favorite part of Turchi’s book is his discussion of Nick Carraway, the narrator of The Great Gatsby. Though most of us were taught to decode the symbolism of the green light or the eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg in order to “solve” what the novel is about, Turchi focuses on the puzzle of Nick Carraway’s personality. Here, the story isn’t one you can solve. Carraway, writes Turchi, “doesn’t recognize his confused and contradictory statements,” and he becomes an incredibly “authoritative narrator whose self-awareness is in doubt.” I know that this is apples-to-oranges, but there’s nothing Fitzgerald could do here to help us “solve” the mystery of Carraway’s personality. Sobol might have butted in: Turn to page 127 for the SOLUTION to “The Case of the Fatuously Judgmental Narrator.” But Turchi resists, because “solving” would mean limiting, reducing.

My favorite part of Turchi’s book is his discussion of Nick Carraway, the narrator of The Great Gatsby. Though most of us were taught to decode the symbolism of the green light or the eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg in order to “solve” what the novel is about, Turchi focuses on the puzzle of Nick Carraway’s personality. Here, the story isn’t one you can solve. Carraway, writes Turchi, “doesn’t recognize his confused and contradictory statements,” and he becomes an incredibly “authoritative narrator whose self-awareness is in doubt.” I know that this is apples-to-oranges, but there’s nothing Fitzgerald could do here to help us “solve” the mystery of Carraway’s personality. Sobol might have butted in: Turn to page 127 for the SOLUTION to “The Case of the Fatuously Judgmental Narrator.” But Turchi resists, because “solving” would mean limiting, reducing.

“We can’t say what woman—or man—will break Nick out of his shell, will meet with his approval. We don’t know what sort of work he’ll do or where he’ll settle down. We don’t know whether he’ll ever recognize the aspects of his character he has unconsciously exposed to us. At the end of the novel, our understanding … of Nick is both multifaceted and incomplete. Both the fragments and the blank spaces are too numerous and consequential for us to assemble a simple whole.”

Besides the pleasure of insights and analyses like these, the book is a beautifully made thing, with color drawings, photographs, crossword puzzles, footnotes, substitution cyphers, riddles, and other miscellany in the margins to play with.

I have a nostalgic fascination for the double image on the cover of this book. Reluctant to add another book to my “to read” stack simply because of the draw of the cover and title, I have willed my self to avoid the temptation of taking the book home. Now you have given a good reason to give in to my desire. Can’t wait to start it. Thank you

AAB