In the summer of 2004 I was 22, poor, recently graduated, and bored at my Washington, D.C desk job. I was frantically checking books out of the Capitol Hill library, hoping something would make my life feel meaningful or tell me where to go next. Nicole Krauss’s Man Walks Into a Room was featured on a display table in the library, and I read it in my too-expensive, too-hot sublet off Constitution Avenue.

In the summer of 2004 I was 22, poor, recently graduated, and bored at my Washington, D.C desk job. I was frantically checking books out of the Capitol Hill library, hoping something would make my life feel meaningful or tell me where to go next. Nicole Krauss’s Man Walks Into a Room was featured on a display table in the library, and I read it in my too-expensive, too-hot sublet off Constitution Avenue.

Man Walks Into a Room is – like much of Krauss’s work – about the nature of memory. Samson Greene, an English professor, develops a brain tumor and suddenly cannot remember anything past his childhood, and then deserts his wife to undergo memory replacement experiments with a Nevada doctor. It is a rich concept with unexpected turns, exceptionally well-written, and I ate it up. But when I got to the end, it became something more.

The short epilogue suddenly switches point of view to that of Anna, the long-suffering wife of Samson. I read it, and was so astonished by it that I sat down and copied it out, word-for-word, in the first page of a brand new notebook. Here is a passage from that epilogue:

We took a drive and stopped by a path on the side of the road. There was a No Trespassing sign, but we ignored it. The sound of a hunter’s gunshots broke the distance. We ducked into a silo—you could see the sky through the gaps in the tin roof, and there were birds up there. Everything, parts I couldn’t have imagined would care, ached for some physical remark of his love. His mouth was cold and tasted metallic, like the season itself, if that’s possible. To me he always seemed like that, autumnal. Painfully earnest, with an awkward swiftness to the way he moved, a physical remoteness like he was already receding. I don’t remember who kissed whom. It was one of those lucid days in which you can see your whole life like a promise before you.

And just like that, at the very end, Man Walks Into a Room becomes a novel also about the nature of love.

And just like that, at the very end, Man Walks Into a Room becomes a novel also about the nature of love.

The two fantastic novels Krauss has written since, 2005’s History of Love and last year’s Great House, also deal with the themes of memory and half-known love, and they bloom out big and fragrant. That the otherwise modest Man Walks into a Room ends where it does, with a mysterious suggestion towards the aching welt at the center of the story, makes sense considering what she would go on to write.

I spent two aimless years in D.C, volunteering for losing presidential campaigns and running out of happy hour money, but after returning to that notebook page where I had copied out the epilogue, I decided what I really I wanted to do was write sentences like those, which articulated what it was to want something inexplicable. It’s safe to say that the epilogue was what made me start something new, a writing program.

On the early autumn day I drove a UHaul away from D.C, it was beautiful: a clear sky trip through the rolling hills of the Blue Ridge, horse farms and vineyards in the distance, green everywhere, and I was alone. It was the only time I didn’t feel sad while moving. It was one of those days, just like I’d read about.

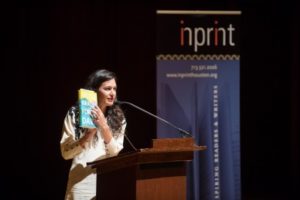

Last Monday’s sudden storms brought uncomfortable reminders of the recent devastation in and around Houston, echoed now in Puerto Rico, and Florida, and other parts of the Caribbean and the Gulf. Those of us who made it to this season’s first installment of the Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series were soggy and a little anxious to come in from the rain. We crowded the orchestra section of Rice University’s Stude Concert Hall, borrowed in the wake of Harvey’s damage to the Wortham Center’s performance spaces.

Last Monday’s sudden storms brought uncomfortable reminders of the recent devastation in and around Houston, echoed now in Puerto Rico, and Florida, and other parts of the Caribbean and the Gulf. Those of us who made it to this season’s first installment of the Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series were soggy and a little anxious to come in from the rain. We crowded the orchestra section of Rice University’s Stude Concert Hall, borrowed in the wake of Harvey’s damage to the Wortham Center’s performance spaces.