The 2018-2019 Inprint Reading Series Kicks Off with Insight, Obsession, and Humor

October 2, 2018, by Charlotte Wyatt

Last Monday night marked the first reading of the 38th season for the Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series, only days after the happy news that reader Esi Edugyan’s Washington Black was short-listed for this year’s prestigious Man-Booker prize. (Also listed is Richard Powers’ The Overstory, from which he’ll read in the series’ April installment.)

Last Monday night marked the first reading of the 38th season for the Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series, only days after the happy news that reader Esi Edugyan’s Washington Black was short-listed for this year’s prestigious Man-Booker prize. (Also listed is Richard Powers’ The Overstory, from which he’ll read in the series’ April installment.)

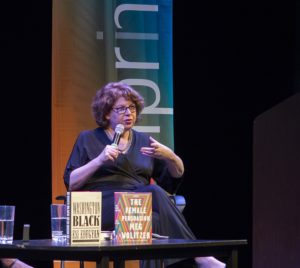

Edugyan read with Meg Wolitzer, and neither author is a stranger to recognition for their work. Edugyan’s previous novel Half-Blood Blues was awarded Canada’s Scotiabank Giller Prize and the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, and was also a finalist for the Man-Booker. Wolitzer’s new novel, The Female Persuasion, was named one of the most anticipated novels of this year by New York magazine, Time, and others, and several films have been based on her work. The most recent is The Wife, starring Glenn Close. (Playing in Houston now!)

After their readings—alternately funny, exciting, poignant, and wise—the authors sat with former Poet Laureate of Houston Robin Davidson, who invited them to share about their process and the timely thematic concerns of both novels.

Edugyan and Wolitzer agreed their fiction tends to orbit “primordial obsessions,” a phrase borrowed from Wolitzer’s previous comments on writing. In this case, their obsessions harmonized as the evening’s readings addressed different modes of dislocation and freedom. Edugyan’s protagonist “Wash” is liberated from enslavement in 19th century Barbados by an adventurer who wants to take him around the world in a flying machine. She spoke of the difficulties the character faces, wrenched from one understanding of the world and placed in another, alien both linguistically and culturally from all he’s ever known. Similarly, Wolitzer’s “Greer” is a college student who experiences an assault that upends her sense of reality—did something happen to her? Was it real? Wrong? How could she tell?

Edugyan and Wolitzer agreed their fiction tends to orbit “primordial obsessions,” a phrase borrowed from Wolitzer’s previous comments on writing. In this case, their obsessions harmonized as the evening’s readings addressed different modes of dislocation and freedom. Edugyan’s protagonist “Wash” is liberated from enslavement in 19th century Barbados by an adventurer who wants to take him around the world in a flying machine. She spoke of the difficulties the character faces, wrenched from one understanding of the world and placed in another, alien both linguistically and culturally from all he’s ever known. Similarly, Wolitzer’s “Greer” is a college student who experiences an assault that upends her sense of reality—did something happen to her? Was it real? Wrong? How could she tell?

Though Wash experiences bodily freedom, the echoes of slavery inform his choices and sense of agency. As Greer’s experience of reality is both contracted and expanded by the narratives of others around her, her agency is also tested. Both writers spoke of creating fiction in a world in flux, where different generations, as well as individuals from vastly different backgrounds, are forced to confront the same crises together despite their unique perspectives.

Davidson drew the similarities between the projects to a point by asking both Edugyan and Wolitzer what they believed the role of the writer should be in contemporary political and social movements. Edugyan explained her interest in suppressed histories, those peoples and communities she had “no idea existed,” and that unearthing and telling their stories felt relevant in today’s social atmosphere. Wolitzer said she believed any personal obsession, political or otherwise, would find its way into her work, and highlighted the role humor could play in imparting the subtle realities of lived experience.

The discussion ended on what felt like an appropriate and important note: when Davidson asked the authors to discuss the craft element called “point of view” in fiction—Edugyan’s novel is written in “first person,” Wolitzer’s in “third”—they agreed writers should position themselves as close or far from a character’s voice as they feel grants the most liberty to explore their obsessions.

Both writers offered visceral and measured perspectives on these smart, incisive fictions, blending insight with humor and wonder, setting a high bar for the rest of what promises to be an outstanding season.