Physician turned writer, Michael Lieberman talks about his work

January 19, 2015, by Inprint Staff

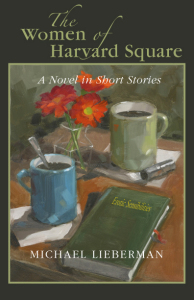

This month Mike Lieberman, Houston poet and novelist, came out with his third novel, The Women of Harvard Square. We caught up with Mike this week to talk to him about his prolific writing life.

This month Mike Lieberman, Houston poet and novelist, came out with his third novel, The Women of Harvard Square. We caught up with Mike this week to talk to him about his prolific writing life.

For those of you who do not know him, in addition to his literary accomplishments, Mike is a former research physician who chaired the department of pathology at Baylor College of Medicine for many years and was also the founding director of The Houston Methodist Hospital Research Institute. He is a member of the Inprint Advisory Board and on the Board of The Jung Center of Houston. A graduate of Yale College, he received his M.D. and Ph.D. degrees from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Mike is warm and engaging and he will talk about The Women of Harvard Square and sign copies this Thursday at The Jung Center, 5200 Montrose, at 5:45 pm. The reading is open to the public.

Inprint: Tell us a little bit about The Women of Harvard Square and how it compares to your other novels.

Mike: The Women of Harvard Square (WHS) is a novel in short stories that follows seven women—three in their twenties, three in their fifties, and one in her eighties. They are scientists and writers living in and around Harvard Square in Cambridge, MA. The book captures their lives—their work lives, their relationships with one another, platonic and otherwise, and several men. It’s a brisk read with deep roots, and unlike my first novel, Never Surrender—Never Retreat (NS NR), which was carefully plotted—though characters had a way of rebelling and making their own needs known—WHS simply flowed from my unconscious. The most important thing I’ve learned in writing fiction is that the story is within you, and too much control produces wooden characters and formulaic plots. Agnes, a Harvard undergraduate, gives her eighty-seven year old grandmother Abigail a vibrator—and my unconscious wouldn’t have it any other way.

Mike: The Women of Harvard Square (WHS) is a novel in short stories that follows seven women—three in their twenties, three in their fifties, and one in her eighties. They are scientists and writers living in and around Harvard Square in Cambridge, MA. The book captures their lives—their work lives, their relationships with one another, platonic and otherwise, and several men. It’s a brisk read with deep roots, and unlike my first novel, Never Surrender—Never Retreat (NS NR), which was carefully plotted—though characters had a way of rebelling and making their own needs known—WHS simply flowed from my unconscious. The most important thing I’ve learned in writing fiction is that the story is within you, and too much control produces wooden characters and formulaic plots. Agnes, a Harvard undergraduate, gives her eighty-seven year old grandmother Abigail a vibrator—and my unconscious wouldn’t have it any other way.

Inprint: Your work has mostly been published by small presses. Can you describe what that process has been like for you?

Mike: When I was completing my first novel, in 2010-2011, I had to make a decision, and based in part on my wife Susan’s experience and advice, I decided not to try to find an agent to place the book with a New York publisher. It has turned out to be, for me, a very good decision. The likelihood of a research physician in late middle age, whatever the merits of his fiction, finding a major house to bring out his work is vanishingly small. I am thrilled to be working with Paul Ruffin and Texas Review Press in Huntsville. They get my obsession and craziness; in fact they have gotten it since the early nineties when I won a blind-submission, juried poetry competition and they brought out my first full-length book. Which leads to the question of what my expectations are as a writer. I write because I must and to figure out how I feel. I want readers, all writers need readers, but the distraction and pain of pursuing more readers by finding a major national publisher would take me away from writing. That’s too high a price. Besides, today whether an author is published by TRP or FSG he or she has to market, market, market, so I can’t see the upside of New York.

I write because I must and to figure out how I feel. I want readers, all writers need readers, but the distraction and pain of pursuing more readers by finding a major national publisher would take me away from writing.

Inprint: It seems like your writing life is thriving right now. Have you always been interested in creative writing? Have you ever taken any formal creative writing courses?

Mike: In high school I was the poetry editor of the school literary magazine and wrote feature pieces for the school newspaper. Poetry reappeared unbeckoned in my mid-forties. When we moved to Houston, I audited an undergraduate poetry writing workshop at UH taught by Linda Gregg, and Ed Hirsch took me under his wing for a bit and directed me to the Squaw Valley poetry workshops where I worked with Galway Kinnell, Sharon Olds, Bob Hass, and Brenda Hillman. For half a dozen years I taught an Inprint poetry workshop—there is nothing like teaching to learn. And so for better or worse, I feel that I have a sense of craft. Fiction is a different story. In fact I have been dabbling in fiction for some time. In 2001 I was fortunate to win the PEN-Texas Award for Fiction, but with a demanding life in medical research, I had no time to pursue writing. Fast forward a bit. I showed an early draft of NS NR to Dan Stern, a friend and generous teacher, who went through it with me. I subsequently trashed the draft and began anew. Seeing how Dan approached fiction was a game changer. The rest I have learned on my own with the kind help of writer friends and by reading broadly and eclectically—since early December I’ve read or begun books by Karl Ove Knausgaard, Amos Oz, James Baldwin, Jincy Willet, Jean Shinoda Bolen, Adam Nicolson, Homer (Fagles and Pope), and Romain Gary. I’m also in a short story bookclub which has been great: it’s very instructive to listen to intelligent readers talk about what they find in fiction.

Inprint: What is your next project—can you give us a sneak peak?

Mike: I am working on what is undoubtedly my most ambitious project to date. The Houstiliad: An Iliad for Houston is a book length poem in which I have appropriated Homer’s characters and set them in conflict in contemporary Houston. Achilles is an MIT-trained engineer who has dropped out and cruises the streets on an old BMW motorcycle with a sidecar looking for trouble. Helen is a young River Oaks matron, and Patroclus, Achilles’ closest friend and second in The Iliad, is, in my poem, a white macaw. Hector is the scion of a wealthy Latino family, the Martillos, hence the moniker “Hector the Hammer”. So it is not a simple retelling of Homer’s story. Although laced with humor, it is a serious look at what drives Houston. The Iliad is about the wrath of Achilles—which Homer announces in the first line. The Houstiliad examines the rage of modern men. Texas Review Press will bring it out in the fall. It is an act of commitment and faith on their part—to publish a book-legnth poem. Even good fiction writers struggle to find an audience.