Salman Rushdie and the Art of Allusion

November 23, 2015, by Doni Wilson

Best known for The Satanic Verses and the Booker Prize-winning Midnight’s Children, Salman Rushdie charmed the audience at his sold-out Inprint reading on November 9th as he read from his new novel, Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights.

Best known for The Satanic Verses and the Booker Prize-winning Midnight’s Children, Salman Rushdie charmed the audience at his sold-out Inprint reading on November 9th as he read from his new novel, Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights.

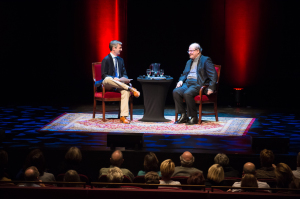

It was a full house in the Cullen Theater at the Wortham Center, a night that was not exactly cold, but not so hot and humid. You could walk through the city all night if you wanted, but once the lights dimmed, you were happy to be waiting for Rushdie to come out, and he disarmed everyone immediately by waving at the audience. It made you feel like he was happy to be in Houston, a place he has been before, including the day before 9-11.

Rich Levy, executive director of Inprint reminded us of how many awards Rushdie has won—and the list is long. It is his third appearance with Inprint, and Levy explained that he was born in Mumbai before the partition of India, but when he speaks, Rushdie seems like a Londoner to me, more like Cambridge than anywhere else. Now, he lives in New York. It is amusing and inspiring when Levy reports that Rushdie started out as a copy writer for the famous advertising firm Ogilvy and Mather.

Ibn Rushd, the hero of his new novel, is a scholar committed to recovering the legacy of Aristotle, so right away the fusion of the east and the west is established in a way that winds itself through the entire novel. The allusion hovering over the narrative is to A Thousand and One Nights, a work Levy tells us prompted this response from Rushdie in a 2006 interview:

“You constantly question these stories….the arguing never stops.” In a way, that is exactly what Rushdie is always interested in: what is “truth,” and who has the authority over establishing what that means in narratives covering divergent times, places, and genres. Each allusion he employs, whether Asian or American, ancient or au courant, makes the case that that is always in dispute, never something that can garner consensus, always keeping the reader on his or her toes. Like the “true nature of the jinn” he dramatizes, truth itself is protean, elusive, “hotly disputed.”

“You constantly question these stories….the arguing never stops.” In a way, that is exactly what Rushdie is always interested in: what is “truth,” and who has the authority over establishing what that means in narratives covering divergent times, places, and genres. Each allusion he employs, whether Asian or American, ancient or au courant, makes the case that that is always in dispute, never something that can garner consensus, always keeping the reader on his or her toes. Like the “true nature of the jinn” he dramatizes, truth itself is protean, elusive, “hotly disputed.”

When Rushdie takes the stage, he discusses writing in a world that has “become very strange and out-of-joint” and using the tradition of the fairy tale juxtaposed with doses of realism to create an effect requiring an appreciation of both. He said of his new novel, “Like most fairy tales, it is about reality.”

Prefacing his reading with a definition of the jinn (“they wreak mayhem because that is what they do’) and a note on the characters he creates, you can start to see what he means. He revealed to the audience that “most of the characters are not exceptional people” and that this “asks the question…which is, how do ordinary people in the middle of their lives deal with the extraordinary?” Suddenly, the fairy tale doesn’t seem so long ago and so far away, but something immediately useful. How, indeed, do we deal with the “disruption” that will characterize the lives of most people? Rushdie explained: “Ordinary people find in themselves unexpected qualities…unexpected resources that they didn’t know they had at their disposal.”

Suddenly, the fairy tale doesn’t seem so long ago and so far away, but something immediately useful. How, indeed, do we deal with the “disruption” that will characterize the lives of most people? Rushdie explained: “Ordinary people find in themselves unexpected qualities…unexpected resources that they didn’t know they had at their disposal.”

This is “the real story that this book is telling…although told in an unreal way.”

As Rushdie reads, you can tell that even though situated in 12th century Spain, under the Moorish conquest of Spain, the novel has a stirring contemporary relevance as he talks about the “forcibly converted Jews” who have to live under an oppressive religious correctness, and the microcosmic representative of such a situation as exemplified by his hero, who is a philosopher who is “not allowed to pursue philosophy.” The correlations between inauthenticity due to social and cultural pressures is not something unique to the territory explored in fairy tales—even modern ones—but rather a fantastic representation of the political and theological correctness characterizing contemporary life in both the West and the East. So when he starts reading ahead in the novel leaping 900 years later to “something very much like now,” in a way, we are already there.

Rushdie reads at length from a section about a New Yorker of Indian origin who works as a landscape gardener, but is disoriented as he literally loses the feeling of the ground beneath his feet, describing it as “then the strangenesses begin.” They are not only physical, but the estrangement that lives encounter anyway, regardless of physical circumstances. As interesting as the narration is Rushdie’s fascination with the nature of narrative itself, how “history…is overwhelmed by legend,” and how we ourselves write history in a particular way. For history is not really verifiable truth, but rather “the story of our ancestors as we choose to tell it.”

Rushdie reads at length from a section about a New Yorker of Indian origin who works as a landscape gardener, but is disoriented as he literally loses the feeling of the ground beneath his feet, describing it as “then the strangenesses begin.” They are not only physical, but the estrangement that lives encounter anyway, regardless of physical circumstances. As interesting as the narration is Rushdie’s fascination with the nature of narrative itself, how “history…is overwhelmed by legend,” and how we ourselves write history in a particular way. For history is not really verifiable truth, but rather “the story of our ancestors as we choose to tell it.”

We warm to his character, Mr. Geronimo, whose name itself reminds us of Rushdie’s striking use of allusions: they are unexpected, but still fit, as Geronimo experiences “the small betrayals of the body” and hoards since he “expected emergencies” and “expected the worst.” We are in a fairy tale, but our human frailties are instantly relatable, recognizable, full of idealism and tragedy simultaneously, just as the historical allusion to “Geronimo” inevitably suggests. Rushdie is a master of reminding the reader and the listener that the extraordinary is so much like the ordinary.

Alexander Parsons, novelist and faculty member in the University of Houston Creative Writing Program, asked Rushdie about the irony of Geronimo’s characterization—a down-to-earth man whose feet leave the ground—and his “losing the ability to feel the earth,” feeling grounded.

Alexander Parsons, novelist and faculty member in the University of Houston Creative Writing Program, asked Rushdie about the irony of Geronimo’s characterization—a down-to-earth man whose feet leave the ground—and his “losing the ability to feel the earth,” feeling grounded.

Rushdie calls this tension “his great obsession,” and confesses his admiration for certain writers so closely connected to a sense of place, how he “envied writers whose feet are firmly on the ground,” particularly those of the American South having “that sense of belonging to a patch of the earth.” He mentions Faulkner, Welty, O’Connor, and we see what he means.

Then things got really interesting as Rushdie spoke about “the colossal social pressure around roots…belonging,” and yet the contrary trajectory that also takes up a lot of real estate in the collective imagination: “the other impulse: the impulse to leave.” He cites the whole tradition of travelers in literature, and life, who resist the “longing for belonging,” are part of the complex mix of the tension between “the pull of home and the pull of away.”

We have our “elected affinities” (our “chosen family’) and then the forces of history and circumstances. Both of those are connected to love and its disruptions: Rushdie comments on how his books address the issue of broken love affairs, often those broken by loss or death, and how “maybe one of the things people do is try to fill that hole…fill the whole of the beloved.” After all, love is “something that we have to construct out of loss.”

Rushdie comments on how his books address the issue of broken love affairs, often those broken by loss or death, and how “maybe one of the things people do is try to fill that hole…fill the whole of the beloved.” After all, love is “something that we have to construct out of loss.”

In the midst of the Q and A, we get a little class on what Rushdie calls “the two ways to write a novel: either it is “an everything book” which “tries to be a universe” or “an omnibus,” in which “you try to include as much as you can get in,” or, its opposite, in which you focus on something smaller and more specific: “Take one shining hair from the head of the goddess.” In other words, “take one thing and make it beautiful.” He also tells us that if you are going to use the fantastic, as he does in his new novel, you better be “a complete realist about it.” Like love and hate, there is a fine line between the real and the fantastic, and Rushdie’s allusions, whether to Kafka, Geronimo, jinn, or Stanley Kubrick, remind us that they are all related if they can all be on our radar simultaneously: contested “truth” makes anything fair game in the realm of the novel.

In the midst of the Q and A, we get a little class on what Rushdie calls “the two ways to write a novel: either it is “an everything book” which “tries to be a universe” or “an omnibus,” in which “you try to include as much as you can get in,” or, its opposite, in which you focus on something smaller and more specific: “Take one shining hair from the head of the goddess.” In other words, “take one thing and make it beautiful.” He also tells us that if you are going to use the fantastic, as he does in his new novel, you better be “a complete realist about it.” Like love and hate, there is a fine line between the real and the fantastic, and Rushdie’s allusions, whether to Kafka, Geronimo, jinn, or Stanley Kubrick, remind us that they are all related if they can all be on our radar simultaneously: contested “truth” makes anything fair game in the realm of the novel.

When asked how he “does it,” Rushdie is modest: He tells everyone, “as a writer you never know where it comes from. You are just grateful it shows up.” He tells us writers, if they are any good, must have “the gift of the ear and the gift of the eye” in order to “see the world as strange as it actually is.”

When asked how he “does it,” Rushdie is modest: He tells everyone, “as a writer you never know where it comes from. You are just grateful it shows up.” He tells us writers, if they are any good, must have “the gift of the ear and the gift of the eye” in order to “see the world as strange as it actually is.” In this way, Rushdie can combine the “storehouse of fabulist literature” from his native India with the immediate allusion to a Magritte painting housed in Houston’s own Menil collection—a juxtaposition of the “sea you are swimming in” when you grow up within a tradition of fantastic literature and are also exposed to the surrealist Western tradition—you can have the magic of both worlds as you “make it strange” in order to reveal the familiar. Both are in the service of “saying something truthful about human beings…literature is about the truth.” But what makes Rushdie’s version of the “truth” so delicious is his ability to make us “see the marvelous” and “remove the veil of habituation.” He has done in fiction what we have been unable to do in real life as he reminds us of the controversies surrounding The Satanic Verses as well as the political climate in present day India which has proved to be a threat to freedom of artistic expression: He has yoked “the Western fantastic with the Eastern fantastic” melding the elements of both. Perhaps it could be a model for how we could strive for more compatibility with Western and Eastern culture here on earth, where we still have our feet on the ground, not yet given the levitation that only the jinn and angels can seem to provide. He reminds us that “realism” is really “a johnny-come-lately” in the history of literature” but “acts like it is the only game in town.”

When asked how he “does it,” Rushdie is modest: He tells everyone, “as a writer you never know where it comes from. You are just grateful it shows up.” He tells us writers, if they are any good, must have “the gift of the ear and the gift of the eye” in order to “see the world as strange as it actually is.” In this way, Rushdie can combine the “storehouse of fabulist literature” from his native India with the immediate allusion to a Magritte painting housed in Houston’s own Menil collection—a juxtaposition of the “sea you are swimming in” when you grow up within a tradition of fantastic literature and are also exposed to the surrealist Western tradition—you can have the magic of both worlds as you “make it strange” in order to reveal the familiar. Both are in the service of “saying something truthful about human beings…literature is about the truth.” But what makes Rushdie’s version of the “truth” so delicious is his ability to make us “see the marvelous” and “remove the veil of habituation.” He has done in fiction what we have been unable to do in real life as he reminds us of the controversies surrounding The Satanic Verses as well as the political climate in present day India which has proved to be a threat to freedom of artistic expression: He has yoked “the Western fantastic with the Eastern fantastic” melding the elements of both. Perhaps it could be a model for how we could strive for more compatibility with Western and Eastern culture here on earth, where we still have our feet on the ground, not yet given the levitation that only the jinn and angels can seem to provide. He reminds us that “realism” is really “a johnny-come-lately” in the history of literature” but “acts like it is the only game in town.”

Rushdie reminds us that in the novel, there is always room for a new game, a new juxtaposition, jinn and New York, the gritty real and the flights of the unreal, and they can occur all at the same time, if you have enough imagination for it.